Narrative

1) Q: What does the word “narrative” mean to you?

A: A narrative is the description of an action, event, or series of events that unfold(s) over time. It is essentially the telling of a story.

2) Q: How important is chronology in a narrative? Can you think of any examples of non-chronological narratives?

A: Students may cite examples of novels (The Sound and the Fury, Absalom and Absalom, The English Patient, Catch-22, One Hundred Years of Solitude) or films (Citizen Kane, Memento, Pulp Fiction). Call students’ attention to techniques such as foreshadowing and the use of flashbacks or disrupted narrative.

3) Q: Why might a narrator deviate from strict linear chronology to make use of these techniques?

A: The narrator may wish to heighten suspense, fear, anticipation, or surprise; to modulate dramatic pacing; to build emotional tension; to aid in character development; or to create ambiguity and nuance. Ask students to refer to specific literary or artistic examples.

4) Q: Have you ever read a book and then seen the movie version (or vice versa) and noticed many differences between them? How might the story change again if represented in a painting? How might fundamental differences among the three media (books, movies, and paintings) influence these changes?

A: Note that narratives are always selective and subjective. Narrators tell their stories in different ways—emphasizing, eliminating, slanting, or reordering events as they see fit. Changes in storytelling may be influenced by differences in political agenda, personal perspective, thematic emphasis, intended audience or market, or creative processes (e.g., a book or painting created by one person vs. a film written by committee).

Modifications are also dictated by the special conditions of the medium. Compare, for example, a moving picture to a static painting; an event you see visually realized on a screen or in a frame to an event you read about and imagine in your head; a film that is finished in 90 minutes to a book you read for three days.

5) Q: A movie, a comic strip, and a painting are all forms of pictorial narrative. How would telling a story in a painting differ from telling a story in a movie or comic strip?

A: The single, unified pictorial format of a painting makes serial exposition of multiple episodes difficult. Comic strips and movies are processed in a predetermined sequence, whereas the eye can move freely through a painting. A movie can directly represent movement and change, whereas a painting (and a comic strip) can only suggest movement and change.

6) Q: Imagine you are a painter trying to represent a story: Goldilocks and the Three Bears. Can you think of pictorial strategies that would help?

A: Allow the students to brainstorm and then guide the discussion toward some of the techniques discussed in the essay. Illustrate with examples of Italian narrative paintings, such as:

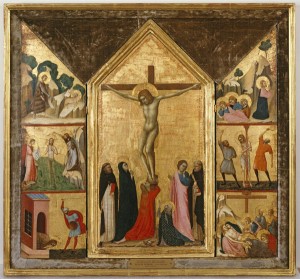

- Multipartite formats

Attributed to Lippo di Benivieni

The Crucifixion with Scenes from the Passion and the Life of St John the Baptist, c. 1315–20

Tempera on wood panel, dimensions by panel: 63.5 x 17.5; 63.5 x 34.3; 61 x 16.5 cm (25 x 6 7/8; 25 x 13 1/2; 24 x 6 1/2 in.)

Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, Gift of the Samuel H. Kress Collection - Expanded pictorial space

- Continuous narrative