Giusto de’ Menabuoi

Polyptych, detail of the lives of holy figures, 1360–62

Tempera on panel

Baptistery, Padua, Italy

Photoservice Electa/Marco Ravenna/Art Resource, NY

The serial approach to narrative in such triptychs buttressed a specific devotional practice in which worshipers pictured in the mind’s eye a sequence of sacred moments (such as Christ’s suffering and death during the Passion) while meditating and praying. The anonymous author of The Garden of Prayer (1454) advised his young female readers on how this episodic form of contemplation could cumulatively build up pious sensations of compassion and remorse:

Alone and solitary, excluding every external thought from your mind, start thinking of the beginning of the Passion, starting with how Jesus entered Jerusalem on the ass. Moving slowly from episode to episode, meditate on each one, dwelling on each single stage and step of the story. And if at any point you feel a sensation of piety, stop: do not pass on as long as that sweet and devout sentiment lasts.3

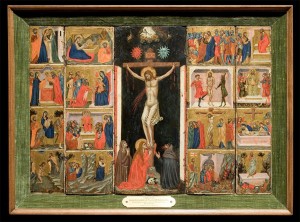

Follower of Pacino de Buonaguida

Ciborium illustrating Sixteen Scenes from the Life of Christ, c. 1325

Tempera and gold on wood panel, 44.5 x 63.5 cm (17 1/2 x 25 in.)

University of Arizona Museum of Art, Samuel H. Kress Collection

Multiepisodic pictorial programs such as those in the two triptychs discussed above provided templates for meditation. The worshipper would process the painted scenes, like the mental images, by “moving slowly from episode to episode, meditat[ing] on each one.” Over time, such paintings would be committed to memory, serving as vivid mental models that the worshiper could draw upon at will.

![Benvenuto di Giovanni<br />Altarpiece for monastery of Sant’Eugenio, <i>Ascension of Christ</i> [main panel], 1491<br />Tempera on wood<br />Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena](http://italianrenaissanceresources.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/RP_320-237x300.jpg)

Benvenuto di Giovanni

Altarpiece for monastery of Sant’Eugenio, Ascension of Christ [main panel], 1491

Tempera on wood

Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena