Jacopo da Pontormo

Two Men with a Passage from Cicero’s “On Friendship,” c. 1524

Oil on panel, 88.2 x 68 cm (34 3/4 x 26 3/4 in.)

Fondazione Giorgio Cini/Galleria di Palazzo Cini, Venice

1. Two friends consider Cicero

In Pontormo’s portrait, we see two men in sober dress, one gesturing to the page he holds. It appears to be a letter bearing a passage from Cicero concerning friendship. For Cicero, friendship was superior to riches, power, sensual pleasure, and even health; it was a pure state in which loyalty and love were animated solely by affection and respect. It is as friends in a classical mode that the two men are represented in their double portrait—not a very common form in the Renaissance. The Latin text is significant not only for the meaning of the words but also as a work of Roman literature: several humanists wrote nostalgically about how their greatest friendships had been formed as young men during shared hours spent reading ancient authors. Pontormo’s two friends are drawn together by this written page and its ideal picture of friendship—and also by the way the painter placed them close together within a narrow space. The darkness of their robes seems almost to unite their bodies into a single mass, while the neutral background eliminates focus on anything but them, their sentiment, and physical and emotional closeness.

This portrait is probably the one that artist and biographer Giorgio Vasari described as depicting two of Pontormo’s closest friends. One Vasari identified as the son-in-law of a successful glass dealer called Beccuccio Bicchieraio. Since Cicero had addressed his treatise to a pair of sons-in-law, the other man in Pontormo’s painting may have been married to another of Beccuccio’s daughters. Both men were probably merchants or tradesmen rather than patricians. That makes them somewhat unusual subjects for a Renaissance portrait—a fact perhaps explained by the artist’s friendship with them. The work may have been painted for Beccuccio.

Cicero’s words are written in chancery cursive script, the elegant and legible hand that had come to be associated with Italian vernacular. That the quotation appears to be in a letter rather than a book suggests a further meaning. Letters, like portraits, connected friends who were absent from each other. The comparison of their relative merits was part of an ongoing Renaissance debate over the superiority of literature versus painting (see The Making of an Artist).

Portrait of a Friend

Titian

Portrait of a Friend of Titian (Portrait of a Gentleman), c. 1550

Oil on canvas, 90.2 x 72.4 cm (35 1/2 x 28 1/2 in.)

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of the Samuel H. Kress Foundation

This image is another portrait made by an artist for a friend. The inscription reads Di Titiano Veccellio singolare amico (devoted friend of Titian’s). The sitter seems to have wanted to memorialize his affectionate ties to the illustrious painter as much as his own appearance.

2. Pazzi conspiracy

Lorenzo de’ Medici commissioned this medal by Bertoldo di Giovanni to commemorate Lorenzo’s survival—and his younger brother Giuliano’s death—following an attack at the hands of Pazzi conspirators. It happened during Mass on April 26, 1478, in the church of S. Maria del Fiore, Florence’s cathedral.

![Bertoldo di Giovanni<br /><i>The Pazzi Conspiracy Medal: Lorenzo de’ Medici, il Magnifico (1449–92)</i> [obverse]; <i>The Murder of Giuliano I de’ Medici</i> [reverse], 1478<br />Bronze, diameter 6.6 cm (2 5/8 in.)<br />National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection<br />Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art](http://italianrenaissanceresources.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/RP_1711-300x146.jpg)

Bertoldo di Giovanni

The Pazzi Conspiracy Medal: Lorenzo de’ Medici, il Magnifico (1449–92) [obverse]; The Murder of Giuliano I de’ Medici [reverse], 1478

Bronze, diameter 6.6 cm (2 5/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

Sandro Botticelli

Giuliano de’ Medici, c. 1478/80

Tempera on panel, 75.5 x 52.5 cm (29 3/4 x 20 11/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

Giuliano’s murder shocked Florence, and his brother ordered a number of portraits for public display to serve both as memorials and admonitions against other plotters. Botticelli’s painting of Giuliano may have been the prototype for that series. It is larger and more monumental than most of his portraits.

The artist, who was an intimate of the Medici circle, must have been devastated by the loss, but his image is not overtly emotional or even highly expressive. It projects an airless melancholy. Giuliano seems pensive, withdrawn. The open window behind him was a familiar symbol of death, referring to the deceased’s passage to the afterlife and resurrection. Some scholars, pointing to Giuliano’s lowered eyelids, consider his image to have been painted from a death mask.

Others, however, suggest that Giuliano himself commissioned the portrait around 1478—and that it was begun in his lifetime—to commemorate his bond to his beloved Simonetta (discussed earlier), who had died two years earlier. She would be represented by the bird on the windowsill, which is a turtledove, a common symbol of constancy (usually female). It is perched on a dead branch, the only place, according to Renaissance lore, on which doves alight after their mates have died. Lacking documentation, it is not possible to say for certain which version of the commissioning events is true.

Florentine 15th or 16th century, probably after a model by Andrea del Verrocchio and Orsino Benintendi

Lorenzo de’ Medici, 1478/1521

Painted terra-cotta, 65.8 x 59.1 x 32.7 cm (25 7/8 x 23 1/4 x 12 7/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

Commemorative images of Lorenzo were also made following the Pazzi affair. Wax effigies were placed in several churches. One of them was dressed in the actual garments Lorenzo had worn on the day of the attack. The terra-cotta bust may reproduce one of those wax votives. The ex-votos were an expression of thanks for Lorenzo’s deliverance—and a reminder to the populace of what had occurred and who had prevailed.

3. Mourning a friend and mentor

Before this painting was transferred to a canvas support, an inscription on the back of the original wood panel read (in translation), “Lorenzo di Credi, most excellent painter, 1488, age 32 years, 8 months.” It was probably added in the sixteenth century, when Credi’s reputation was at its height. He was one of many students in the busy Florentine workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio, which also included Perugino and Leonardo da Vinci. Giorgio Vasari described the three younger men as friends and rivals.

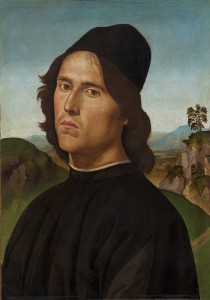

Perugino

Portrait of Lorenzo di Credi, 1488

Oil on panel transferred to canvas, 44 x 30.5 cm (17 5/16 x 12 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Widener Collection

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

The portrait subject’s aquiline nose and jutting chin compare well with another known likeness of Credi (as an older man), and for many years Perugino’s painting was accepted as a self-portrait by Credi. Now, however, it is thought to reveal Credi’s face but Perugino’s artistry. Many landscapes by Perugino have the same silvery quality we see here. Moreover, the strong planes of the face and tousled coiffure more closely resemble Perugino’s bolder style than Credi’s smoother, more polished painting.

The unusual backward tilt of the head reinforces the melancholy mood established by Credi’s sad, distant gaze and set mouth. It has been suggested that Perugino painted this image of Credi just after the death of their beloved master, Verrocchio, in 1488, the same date that was inscribed on the panel. Credi inherited Verrocchio’s drawings, sculptures, and art materials and took over his shop. It had been his unhappy task to accompany Verrocchio’s remains back to Florence for burial after the master’s death in Venice. This painting can be read as an expression of the respect and affection that Credi and Perugino held for each other, and (even more) for their beloved teacher and friend.