Friendship was a subject on the minds of many fifteenth-century Florentines. Merchants and businessmen mused over it frequently in their journals and diaries, often proceeding with the caution expressed by Giovanni Morelli, who advised that a friend should be tested a hundred times before he was trusted once. Another wary writer noted that one enemy can cause more harm than four friends can do to help.

Florence was a city of about forty thousand for most of the fifteenth century; it could be crossed on foot from east to west or north to south in half an hour or so. Its economic and civic life relied on personal connections played out face-to-face. Friends were an extension of family networks and connected through long chains of obligation. As Matteo Palmieri noted in his treatise on civil life, “Friendship is the sole link that binds cities together.”14 As in ancient Rome, a system of patron-client relationships knit the citizenry into webs of social, mercantile, and political exchange. Powerful men assisted and promoted loyal supporters (as when, for example, Lorenzo de’ Medici worked to procure good marriages for his partisans). In return, clients backed their patrons and patron’s friends—and worked to thwart their patron’s enemies.

The Importance of Medals

Sandro Botticelli

Unknown Man, possibly the artist or his brother, with medal of Cosimo the Elder (1389–1464), 1474–5

Tempera on panel, 57.5 x 44 cm (22 3/5 x 17 3/10 in.)

Uffizi, Florence

Alfredo Dagli Orti/The Art Archive at Art Resource, NY

![Bertoldo di Giovanni<br /><i>The Pazzi Conspiracy Medal: Lorenzo de’ Medici, il Magnifico (1449–92)</i> [obverse]; <i>The Murder of Giuliano I de’ Medici</i> [reverse], 1478<br />Bronze, diameter 6.6 cm (2 5/8 in.)<br />National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection<br />Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art](http://italianrenaissanceresources.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/RP_1712-1.jpg)

Bertoldo di Giovanni

The Pazzi Conspiracy Medal: Lorenzo de’ Medici, il Magnifico (1449–92) [obverse]; The Murder of Giuliano I de’ Medici [reverse], 1478

Bronze, diameter 6.6 cm (2 5/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

Even when cemented through family connections, friendships could be quite volatile. Any number of circumstances—business disputes, rivalries, outside pressures—could turn a friend into an enemy. In October 1444, Leon Battista Alberti and Piero de’ Medici organized a juried rhetorical competition (certame coronario), on the nature of friendship. During recitations in Florence’s cathedral, the bonds of friendship were described as “turning like leaves / as the whim strikes us / sometimes for desire and sometimes for disdain.”15 Patronage could easily sour when the onore et utile (honor and profit) of either party was no longer served—as the Pazzi conspiracy (discussed later) illustrates.

Most of those who spoke at the certame coronario, however, had a generally idealized view of friendship. This type of competition was modeled on similar contests mounted in ancient Rome (and was intended to prove that Italian was the equal of Latin). Most submissions presented in 1444, which were quickly copied and widely circulated, drew on De amicitia (On Friendship), a treatise written by Roman philosopher and lawyer Marcus Tullius Cicero. For Cicero, friendship was a pure exercise of virtue that excluded any notion of individual profit or gain. Anselmo Calderoni, who was a herald and entertainer and spoke first at the contest, appealed directly to the Roman’s authority: “I begin with Tulio. . . . He would say that friendship exists only / when with the purest good faith / one loves another.16

Although not always so selflessly practiced within the competitive, mercantile world of Renaissance Florence—or Rome, for that matter—Cicero’s elevated conception of friendship remained a humanist ideal. Within the Medici circle, it was sometimes given a homoerotic cast or presented in the elevating rhetoric of Neoplatonism. Like a platonic affair between a man and a woman (discussed earlier), friendship suggested a capacity to unite with the infinite. Ultimately, the perfect model for human friendship was the bond that existed between man and God. As stories like that of Tobias and the angel reveal, holy personages were the best companions and helpmates of men. But this perfect friendship with God—to which Morelli and other diarists often devoted their thoughts—also carried moral responsibility. Of all friends, Anselmo Calderoni concluded:

the truest I would say, without a doubt, is Almighty God,

who is truly loving to all his friends . . .

I conclude in effect that the friendship of God is perfect,

and never false; and yes, all else is partisanship.17

Tobias and the Angel

Filippino Lippi

Tobias and the Angel, c. 1475/80

Oil and tempera (?) on panel, 32.7 x 23.5 cm (12 7/8 x 9 1/4 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

The apocryphal book of Tobit tells the story of Tobit of Nineveh, a poor, blind man of good faith, who sent his son Tobias to a distant city to collect money he had on deposit there. Worried about his safety, Tobit hired someone to accompany the youth, a companion who turned out to be the archangel Raphael in disguise. Their journey was a success: not only was the money retrieved, but the medicine made from a monstrous fish Tobias encountered along the way also cured his father’s blindness. The story was particularly popular in Florence, where fathers sent many sons on business to faraway lands; networks of friends and connections would aid the young travelers.

Renaissance friendship was an essentially male prerogative. Men developed bonds outside the family through their active lives in the community, through political and business connections and memberships in lay confraternities and other charitable organizations. Women, more or less limited to their households, family gatherings, and occasional appearances in church, had few opportunities to cultivate adult friendships beyond their immediate relations. For some women the convent offered a chance for female companionship—and a way to live a life that was not dominated by the roles of wife and mother. True friendships between men and women must have been quite rare. One notable exception is the friendship of Michelangelo and Vittoria Colonna.

A Gift from Michelangelo

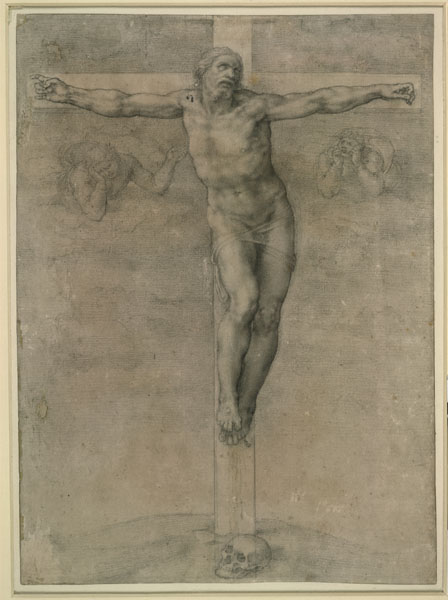

Michelangelo

Christ on the Cross, 1536–41

Drawing in black chalk, 36.8 x 26.8 cm (14 1/2 x 10 5/8 in.)

British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

Michelangelo sent this drawing to Vittoria Colonna, a gifted humanist in Rome with whom he had a long and intimate correspondence. She wrote to thank him for it: “Unique master Michelangelo and my most particular friend, I have received your letter and seen the Crucifix which has certainly crucified itself in my memory more than any other picture that I have ever seen.”18 If their male-female friendship was rare, so was the nature of this gift. It and other drawings the artist gave to male friends are among the first drawings ever made as finished works of art in themselves, rather than as studies. Michelangelo created them as presentation pieces for those closest to him. After Vittoria’s death, he wrote of her as an amico—using the male, not female, form of the word.