The three major monotheistic religions have all struggled with the tension between imagery and idolatry. Within Christianity, iconoclastic controversies have arisen at various times and places. In Byzantium the issue was ardently fought along regional, political, and theological lines during the eighth and ninth centuries. It took more than a hundred years before the issue was settled and the place of images in the Christian tradition secured.

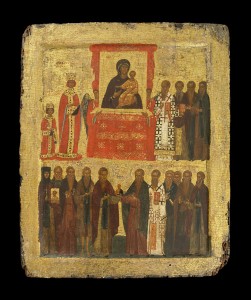

Icon with the Triumph of Orthodoxy

Byzantine (Constantinople), c. 1400

Icon with the Triumph of Orthodoxy

Tempera and gold on panel, 37.8 x 31.4 cm (15 3/8 x 12 3/16 in.)

British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

This icon makes clear the victory of images over iconoclasm, as saints, theologians, and members of the Byzantine imperial family flank the icon of the Hodegetria in Constantinople. The feast of the Triumph of Orthodoxy—that is, the orthodoxy of icons—was first celebrated on March 11, 843. Although this panel was painted some five hundred years later, viewers would have immediately recognized the subject and its import.

One of the arguments advanced in favor of images against the iconoclasts was the existence of acheiropoieta—images “not made by human hands.” The most celebrated of these was the Mandylion of Edessa. According to accounts Christ sent the king of Edessa a cloth on which his visage had been imprinted after he used it to wash his face. The mandylion (“small cloth”) produced many miracles over the centuries. After its transfer to Constantinople in the tenth century, it was viewed as the city’s palladium and was kept in an imperial chapel. Its whereabouts after 1204 are unclear, but copies (or by other accounts, the original) are revered today in Genoa and the Lateran in Rome. The mandylion elevated the idea of the image to a new status.

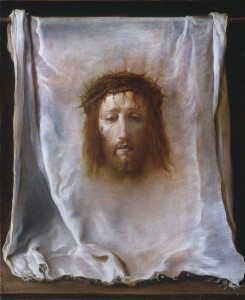

Domenico Fetti

The Veil of Veronica, c. 1618/22

Oil on panel, 80.6 x 66.3 cm (31 3/4 x 26 1/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

In the West the more famous example of an acheiropoieton is the Veronica Veil kept in Saint Peter’s in Rome, depicted in Domenico Fetti’s seventeenth-century painting. The relic is securely recorded in Saint Peter’s by 1199. (“Veronica” is often said, incorrectly, to derive from the words vera icon, or “true icon,” but the name is more likely to result from confusion with another story, about a woman named Berenike.) According to Veronica’s legend, conflated during the Middle Ages from several sources, she gave Christ a cloth with which to wipe his brow as he struggled along the Via Dolorosa to his crucifixion. An image of his face remained imprinted on it. Pilgrims flocked to see the cloth, called either “the Veronica” or the sudarium, Latin for handkerchief. From the fourteenth century it was the most important relic in the West. Long indulgences were granted depending on the length of the pilgrim’s journey: three thousand years for Romans, nine thousand for other Italians, and twelve thousand for those who arrived from outside Italy. Interestingly, and apparently for the first time, an indulgence was gained for reciting the proper prayers, whether in front of the veil itself or an image of it. The sudarium was reproduced countless times, even after the pope prohibited the practice in the early seventeenth century.

The mandylion and the sudarium were not only images but also had the status of relics, objects that had been in direct physical contact with Jesus. Since it was Jesus himself who had created these “true portraits,” those arguing for the legitimacy of religious images reasoned that Christ sanctioned them. For other iconophiles, the legitimacy of religious images grew directly from the absolute identification of the representation and its holy model that is the essence of an icon. Because the honor directed to the image was transferred to its prototype, theologians, East and West, denied that an icon was an idol.

The most fundamental argument in favor of images within the Christian tradition, however, is the Incarnation itself. This central doctrine holds that Christ is equally human and divine. Likenesses, which necessarily showed Christ as a man, were all but required by this reality. They not only illustrated his human nature—they proved it: his infancy, his teachings on earth, the agony he suffered on the Cross. The Incarnation is “present” in all Christian imagery, but it touches especially closely on human experience in scenes of the Virgin and Child where an emotional bond is strongly “felt” to connect Christ’s humanity and the viewer’s.