Fra Angelico and Fra Filippo Lippi

The Adoration of the Magi, c. 1440/1460

Tempera on panel, diameter 137.3 cm (54 1/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

When Roman ruins first entered the painter’s vocabulary in the fifteenth century, they carried a specific religious connotation. Tangible reminders of the demise of a pagan civilization that had once straddled much of the globe, antique ruins appeared to manifest the inexorable workings of God’s will. In Italian Renaissance paintings of the Infancy of Christ, fragments of classical buildings symbolize the old order overturned by the Redeemer’s birth. For example, the arch of a ruined classical building serves as a portal which the faithful must pass through and leave behind on their way to worship the infant Jesus in the foreground of The Adoration of the Magi, c. 1400–55, by Fra Angelico and Fra Filippo Lippi. The derelict arch most obviously refers to the pagan religion of the Romans, which was superseded by Christianity. It also symbolizes the old Temple of Jewish faith (founded on God’s original covenant with Moses) that was superseded by the new Temple, embodied by Christ. As the savior of the world, the infant Christ heralded a new covenant between God and humankind in which mercy and eternal life vanquished sin and death. The painting visualizes this message by juxtaposing the decaying ancient temple, peopled by naked and vulnerable human figures, with Jesus’s birthplace: the intact, modern stable presided over by the outsized peacock, an early Christian symbol of resurrection and immortality.

Attributed to Domenico Morone

Adoration of the Magi, c. 1484

Oil on canvas, 83.5 x 99.3 cm (32 15/16 x 39 1/16 in.)

Columbia Museum of Art, Samuel H. Kress Collection

Columbia Museum of Art

In the upper left corner of Morone’s picture, the statue of a pagan god surmounts a fractured cornice of the building, providing an additional emblem of religious obsolescence. Perched in an arch just below the idol, a peacock reinforces the contrast between the ephemeral and the eternal. The false idol and the newborn Redeemer resemble one another in their nakedness, but while the stone statue is lifeless and neglected, the squirming newborn child embodies divine perfection and the promise of eternal life, bringing the kings to their knees in awed admiration.

Attributed to Domenico Morone

Adoration of the Magi (detail of statue), c. 1484

Oil on canvas, 83.5 x 99.3 cm (32 15/16 x 39 1/16 in.)

Columbia Museum of Art, Samuel H. Kress Collection

Columbia Museum of Art

The Roman ruins seen here and in many other Renaissance paintings hark back to Christian legends in which divine intervention causes the spontaneous destruction of pagan monuments—a stirring alternative to the mundane historical record of war, iconoclasm, and vandalism. According to medieval lore, a temple erected by the Roman emperor Augustus had miraculously imploded on the night of Christ’s birth—an event supposedly foretold by the oracle of Apollo, who had declared that the temple would stand until the day a virgin gave birth to a child, a condition that was fulfilled by Christ’s birth to the Virgin Mary. Along the same lines were reports of the miraculous disintegration of pagan statues, a recurring episode in the lives of saints. One such tale concerns Saint Apollonia (d. 249), a devout Christian of Alexandria, Egypt, who refused to obey the Roman Emperor’s edict commanding public worship of the pagan gods. When Apollonia made the sign of the cross before a stone idol, it reportedly shattered into a thousand pieces.

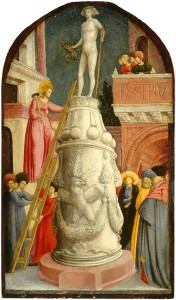

The Venetian painter Giovanni d’Alemagna treated this episode in one of a series of four paintings of c. 1440–50 depicting events in the life of Apollonia. In Saint Apollonia Destroys a Pagan Idol, c. 1442/45, he abandoned the tale of miraculous destruction in favor of a more plausible and pragmatic representation of pious iconoclasm. Apollonia is shown halfway up a ladder, wielding a hammer to destroy a statue of Bacchus, the Roman god of wine and orgiastic excess. Clothing and its absence help dramatize the clash between the pagan and the Christian worlds. The polished sensuousness and lithe form of the nude statue contrast with the enshrouded body of the saint, which is encumbered by volumes of heavy cloth. Bacchus’s nudity reinforces his association with liberty and sensuality, while Apollonia’s gown, which hides her body, expresses her self-abnegating chastity.

Giovanni d’Alemagna

Saint Apollonia Destroys a Pagan Idol, c. 1442/1445

Tempera on panel, 59.4 x 34.7 cm (23 3/8 x 13 11/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Samuel H. Kress Collection

Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art

The painting suggests the manner in which fascination with classical antiquity had begun to shape the selection and interpretation of Christian themes by the mid-fifteenth century. Although Apollonia is the artist’s ostensible focus, it is the lavish monument at the center of the composition that actually commands our attention. Brighter than any other element and executed in an eye-deceiving, three-dimensional style, the monument conveys a palpable impression of material reality that is lacking in the doll-like figures. Ornamenting the marble pillar, the mighty eagle—emblem of Rome—asserts the empire’s dominion over this distant Egyptian province. In the background, polychromatic marble buildings with elaborate arches, inscriptions, and decorative carvings evoke the luxury and ostentation of the imperial milieu.

Concern with archaeological accuracy shaped the painting’s imagery. The artist based the eagle-ornamented pillar on a Roman altar that appears in other Venetian paintings of the period and in an album of drawings by Jacopo Bellini. The nude statue of Bacchus was also likely modeled on ancient prototypes known in Venice. Artists were constantly on the lookout for promising antique models to emulate and adapt. It was standard practice to keep drawings of these objects on hand in their workshops as authentic reference materials. (Read An impromptu pilgrimage.) Artists also amassed a great variety of antique remains, such as marble sculptures and fragments, bronze statuettes, gems, coins and medals, and plaster-cast reproductions. These useful collections provided artists with a repertoire of classical compositions, poses, and decorative motifs that could be adapted to diverse projects. Such collections circulated among artists and often passed from one generation to another. In 1471 Bellini’s widow bequeathed his famous book of drawings to their son Gentile, along with a variety of marble statuary, relief sculptures, and plaster casts.